Oh, another Cornwell, you say? Yep. He's that good - and so is The Burning Land. The auteur author of military Historical Fiction continues his Saxon Chronicles series (Burning Land is the fifth so far) as Uhtred makes his well-worn transition from unmanageable Lord to manipulable outlaw of King Alfred the Great.

Perhaps the greatest commentary on The Burning Land is how much Cornwell ignores background characters and the novel is overshadowed by the one-book character Skade. While Aethelflaed continues to be one of Cornwell's obvious historical heroines, it seems the author has decided consciously to emphasise the "Behind the Scenes" role played by women in the lives of men and highlight how much influence they are able to wield.

Perhaps now, five books in with a remarkable cast of characters, the major ones - Uhtred, Alfred and now Aethelflaed - are given pages of exposition at the expense of minor players: people we've grown accustomed to, such as Finan and Father Pyrlig. This probably reflects their historical and narrative importance as many of those overshadowed are good men but merely - to use a horribly overstated metaphor - pawns, whereas Uhtred is without doubt Alfred's (and Aethelflaed's) destructive queen. This isn't so much a criticism, but merely comment as this chapter of the Saxon tales becomes less to do with the Uhtred/Alfred dynamic and more to do with the big-picture decisions Uhtred faces as he begins to see for once his own final position in Saxon attempts to expel the Danish invasion.

Named for a Norwegian hunting goddess, Skade becomes the enemy that Cornwell's modus operandi demands must be vanquished in the book's final battle. Indeed, not only is a final climactic battle expected of a Cornwellian novel, but also a final arcade-game type "Boss" that Uhtred must confront himself. (With each "Boss", it seems Uhtred gets closer to reclaiming his family's ancestral home, Bebbanburg. It's telling that at least two of his great nemeses remain - his former "man" Haesten and his usurping uncle Aelfric - so expect at least two more books in the Saxon Chronicles). In The Burning Land, that's this maddened "sorceress" and perhaps, of all Cornwell's creations for this great series, the only character who could be described as totally evil. Where others may be selfish, mad or simply cold-blooded, each is portrayed as Uhtred sees them - with increasingly understanding or sympathetic judgement as he ages - but Skade sees him almost intimidated at his inability to identify with her.

As an older man now - probably in his mid-thirties, the Dark Age equivalent of our sixtyish - the hero finds himself identifying more often with opposing forces than in the previous four volumes, often thinking "Had I been Bishop Asser..." or "Had I been in his position...". Meaning that while he's always narrated these books in his dotage as a retrospective of his life as a warrior, for now Uhtred is faced more with his own mortality. In a series - and an era - in which death is common, in this work it hovers over Uhtred's shoulder like a blackbird, always feeling like a nasty twist is looming.

The Burning Land is also notable as the first time Uhtred is catalogued as having made a dire tactical mistake on the battlefield. While he's acknowledged luck before, this is the first time on the battlefield where he's either been out-thought or made a rash error of judgement.

Perspective seems to be the hero's watchword for this fifth volume. Uhtred ages and finally (or so it seems) is forced to choose whether he is a Northman or a Saxon once and for all. This results in his bidding farewell to another aspect of his heritage and once again, it is strong women on each side able to inspire him into the decision. The choice is coloured as one small decision's ability to turn the course of a larger scenario, serving to further highlight Uhtred's maturation from a brash, but resourceful fighter into an imposing Warlord; able to inspire fear not only because of his physical stature but also through his reputation and guile.

Coupled with his increasing ability to politic and interactions with two Christian priests who enter the narrative at the novel's climax, Uhtred becomes less definite and able to see not just in absolutes. He in fact becomes more well-sketched as a human, following in the succession of Cornwellian flawed heroes -like Thomas of Hookton and Derfel Cadarn - who matured from character to human.

The Saxon Chronicles: The Burning Land, by Bernard Cornwell receives footballs.

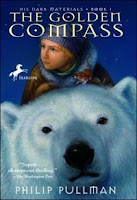

Cover image courtesy: en.wikipedia.org